What are the main objections raised to my manifesto and what is my response?

What are the main objections I have encountered?

The main pushback I have received to my manifesto falls into one of two camps:

“What’s done is done”. The Covid era is thankfully very much in the past and our focus should be on improving the future. Whilst we might gain something from reviewing the Covid decisions more closely, it is not clear why this should be a priority.

“Not a job for the IFoA Council”. The role of Council is to steer the profession in the interests of its members. It is not clear how the manifesto fits with this.

I understand why some of my peers react with these “Pushback Perspectives” and so I have set out a detailed response in this section.

High level answer: “Bad Heuristics”

The issue with both Pushback Perspectives is that they fail to appreciate the bigger picture. This bigger picture is that the response to Covid illuminates there are deep-seated issues in our decision making which need to be rooted out, otherwise they will likely undermine the future prospects of the UK and consequently undermine the actuarial industry (much of which depends on the economic stability of the wider country).

I would describe my assessment of the situation to be as follows:

The Covid response was a disaster for the UK because the costs incurred far outweighed any benefits (both financial and non-financial).

The Covid response was driven by the thinking of the UK’s decision makers.

That thinking was flawed due to some “Bad Heuristics” which have taken root in the national mindset.

These Bad Heuristics are still present and have the potential to corrupt future decisions.

Unless these Bad Heuristics are confronted then there is every risk that their influence will cause future mistakes which destabilise the country further (perhaps irreparably).

The one positive is that the Covid response affords us an opportunity to bring these Bad Heuristics into the light and neutralise them.

Achieving this resolution is critical to the future success of the UK and the IFoA. My three SMART investigations will not singlehandedly achieve this, but I do believe they can facilitate the meaningful evaluation of the Covid response which will bring these benefits.

I appreciate this is a bold assertion to make. I have provided justification in the subsections below, but I trust this overview provides a quick answer to the pushback.

I also want to take this opportunity to appeal to my peers based outside the UK. I will maintain a UK focus in this response but I believe that much of what I say applies beyond the shores of Britain (especially given the level of international conformity in responding to the Covid crisis). Moreover, whilst my manifesto proposes investigations from the perspective of the UK, I am confident the results of this activity will have wider applications.

I have structured the remainder of my response by looking at each Bad Heuristic in turn:

1. Demonising dissenters

2. Failing to see the “civilisational forest” from the “trees” of the day-to-day system

3. Elevating mathematical modelling to the status of science

In each case I will endeavour to provide context for what the Bad Heuristic relates to, how they satisfy the “Pushback Perspectives” and how my investigations address the problem.

Bad Heuristic 1: Demonising dissenters

Can anyone dispute that polarisation is a growing problem across the West? In less than a decade we have witnessed:

The Brexit tensions within the UK

The rise of Trump in the US

The growth of anti-establishment political parties across Europe

Fundamentally this is driven by an increasing number of people being critical of the status quo. These people might be correct in their thinking, they might be wrong, that is beside the point: the critical issue is that we seem to have lost mutual respect and our ability to resolve differences using constructive debate.

This is deeply worrying. Where are we without dialogue? A wise man once said, “There is a word for someone you can’t talk to: that word is enemy.”

We saw this during the Covid crisis where a rift arose between those strongly supportive of the measures and the critics. Truth be told, ad hominems flew both ways. However thanks to the imbalance of power it was the dissenters against the Establishment consensus who were most demonised and even censored (sometimes just for asking reasonable questions).

At this point I strongly urge you, the reader, to reflect on the period of 2020 and 2021: how did you react at this time if you encountered a friend or family member questioning the response?

All of this is indicative of the first Bad Heuristic which I perceive to be poisoning the UK’s decision making: an intolerant Group Think which is prepared to use Establishment power to shut down dissenters. I regard such Group Think as a danger to a well-functioning society and in this view I am supported by previous work published by the IFoA as part of its activities with the Joint Forum on Actuarial Regulation (“JFAR”). In particular I would point to the JFAR review of Group Think published in June 2016, which recommended that we “ensure all views are heard”.

Yet how well did the IFoA stand up for this principle when one of its members, Nick Hudson, raised a dissenting voice in April 2020 by creating the organisation “PANDA” which focused on challenging the Covid orthodoxy (rightly or wrongly)? Did the IFoA facilitate good faith debate between this critic and the apologists for the Covid response, helping to bridge the divide in an effort to counteract the destabilising polarisation of society? When Nick Hudson was literally censored from mainstream platforms as he sought to make his case, did the IFoA help to ensure his argument was given fair hearing?

Please ponder this question seriously: do you think failing to give dissenters a fair hearing helps to defuse the problematic polarisation we are seeing or does it make it worse?

My Investigation 1 will not fix the problem of polarisation. But it has the potential to work some healing. By extending the Covid critics (like Nick Hudson) a chance to put forward a “steel man” version of their concerns in a transparent forum where it will be given fair hearing but also subjected to robust rebuttal, we show dignified respect to those we may disagree with and enable our society to move forwards with less division than it has now.

Moreover, this will give the IFoA an opportunity to provide a tangible example of how to address the challenge of Group Think. This activity can only reinforce our credibility on this important issue, which we previously raised as part of the JFAR review published in 2016.

Lastly, I wish to flag that there is an actuarial interest in the conclusions of Investigation 1. We must appreciate that any failings in the development or roll-out process of medical drugs has the potential to incur losses for the insurance industry. It is in our direct financial interests to be confident that these processes are robust. This is not to say that Investigation 1 will find any problems, but what is the downside with pursuing this sober assessment?

Bad Heuristic 2: Failing to see the “civilisational forest” from the “trees” of the day-to-day system

Some may disagree, but I believe the UK’s politicians and civil servants have become so focused on maintaining our current State systems that they have lost sight of what purpose each one is meant to serve. In particular I sometimes get the impression that those in charge have inverted the key relationships, such as:

Instead of the NHS being in place to meet the health needs of the nation, people are encouraged to adopt healthier behaviours to help the NHS.

Instead of fostering an economy that secures good lifestyles for wage-earners over the long-term, workers are viewed as economic units to boost GDP.

Instead of identifying an appropriate level of public service provision and judiciously calibrating taxation accordingly, the government considers the maximum amount of money it can plausibly raise from the populace and then budgets accordingly.

I credit the IFoA with undertaking work which combats this failing (at least to some extent). In particular the IFoA has produced policy papers on the subject of “intergenerational fairness”, which provided a reminder of who the UK’s systems are meant to be serving by highlighting the importance of balancing the needs of different generations.

In truth, I think the IFoA’s framing is not quite correct. I would be advocating for intergenerational unfairness, specifically because I want my son to enjoy a more prosperous life than mine and I hope he will pay this forward to his children in the same vein. This “Civilisational Attitude” is how nations flourish: by focusing on how best to improve the lot of the upcoming generations and prioritising policy towards this.

This is an area where the UK has arguably been struggling. For example, the decision to maintain artificially low interest rates throughout the 2010s was a boon to the asset-rich at the expense of the asset-poor. Most notably this disadvantaged younger people struggling to buy their first home because it fuelled a strong surge in house prices.

However the response to Covid really stands out as the antithesis of the Civilisational Attitude. Remember that COVID was primarily a threat to the older generations. The young were not entirely immune but the threat was significantly weaker. Yet the reaction to this crisis was to spend a vast sum of money (estimated at ~£350bn of government spending, >10% of total national debt) on an attempt to mitigate the number of premature deaths that were principally occurring amongst the oldest cohorts.

It is worth stressing that this £350 billion was not an investment. The UK does not have £350bn worth of schools, hospitals or other infrastructure to show for this spending. What taxpayers do have is an extra £350bn worth of national debt to service, which will need to be covered by deductions from the wages of the young working population and the profits of their employers (including many members of the IFoA).

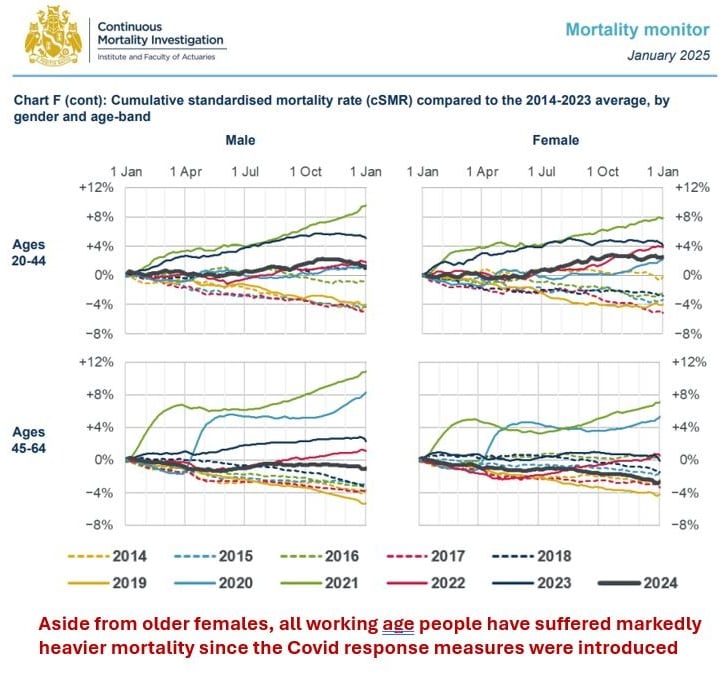

Most concerning of all, there is some evidence to suggest that the Covid interventions have had a detrimental impact on the mortality rates of the working age population. The underlying cause(s) are still being explored, but it is an objective fact that the UK has experienced sustained heavy mortality in the working age population since 2020. This is well-illustrated by the CMI’s quarterly mortality monitors, which clearly show consistently and markedly higher age-standardised mortality experience for the years 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024 compared to the pack of lines corresponding to pre-pandemic norms:

Arguably the COVID response was the single worst act of peacetime policy to disadvantage the young in favour of the interests of the old, i.e. intergenerational unfairness at its worst. But please don't place any blame on the older generations - they did not ask for this and, had older people been presented with the choice, I have little doubt that they would have selflessly opted to prioritise the interests of their children and grandchildren over their own needs. No, this misguided action is indicative of the second Bad Heuristic which I perceive to be poisoning the UK’s decision making: specifically decision makers fail to register the importance of the Civilisational Attitude because they are too preoccupied with the short-term demands of the systems they are maintaining.

There is surely a case for the IFoA to further public thinking around intergenerational fairness by exploring this subject in more depth. Investigation 2 will help in this area by assessing what the benefits were from the Covid response (if any) and how the mortality rates of younger generations in different countries have been affected in the wake of the pandemic.

I note this is effectively an extension of the work conducted by the CMI in Working Paper 180. However the CMI is (rightly) constrained by the strict remit governing its activities, so my aspiration is that Investigation 2 can bring further important insights into the public space around this topic (and I would take this opportunity to signal my gratitude to the CMI for conducting this work as it gives me a clear starting position in terms of methodology and data sources).

Bad Heuristic 3: Elevating mathematical modelling to the status of science

Our modern societies rightly treat science with the highest respect. We often take for granted the technological wonders that science has given us and we are all truly privileged to have access to the unprecedented wealth that even the poorest members of society enjoy.

We are also fortunate that science has a “cousin” in the form of mathematical modelling. This area has become a mainstay of actuarial work and is one of the ways in which the profession adds considerable value when assisting the efforts of key business decision makers.

However things can go wrong when mathematical modelling is confused with its scientific cousin. Science can be counted on with virtual certainty, whereas mathematical modelling provides guidance of varying levels of reliability: science is like using the GPS on a mobile phone for navigation, whilst mathematical modelling may be more like interpreting a badly drawn map. It is vital that decision makers understand and take account of the inherent uncertainty in any information derived from mathematical modelling and do not simply treat it with the credence which science warrants.

The world experienced a devastating example of the mis-application of mathematical modelling with the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. The IFoA appreciates the importance of best practice to mitigate the risks associated with modelling and this is one reason the IFoA expects members to adhere to the Technical Actuarial Standards.

Clearly mathematical modelling played a large part in guiding the response of the UK Government during the Covid crisis. However, what is less clear is the extent to which both the mathematical modelling and the communication of the results satisfied what the IFoA would consider to be best practice in these activities. This is a genuine concern in some quarters; for example, in December 2021 the editor of the Spectator magazine had a Twitter exchange with a prominent modeller of the Omicron variant and ultimately published this statement:

“In my view, this raises serious questions not just about Sage but about the nature and quality of the advice used to make UK lockdown decisions. And the lack of transparency and scrutiny of that advice. The lives of millions of people rests on the quality of decisions, so the calibre of information supplied matters rather a lot — to all of us.”

This Spectator article sits alongside an unflattering comparison of the Sage modelling scenarios with actual experience: https://data.spectator.co.uk/category/sage-scenarios

This anecdote is suggestive of the third Bad Heuristic, whereby mathematical modelling is inappropriately treated as science. I acknowledge that this Bad Heuristic is less clearly present than Bad Heuristic 1 and Bad Heuristic 2 described above. Nonetheless there is something worthy of investigation which has ramifications for the future: we should expect that mathematical modelling will be used to guide important decisions in future crises and so it is important that we learn any lessons now.

Moreover the actuarial profession should treat this as an opportunity. Evaluating the use of mathematical modelling beyond our traditional business settings and identifying improvements could open up more career openings for actuaries by revealing new places where our skillset can add significant value (financial or otherwise).

Investigation 3 is targeted in this area: it seeks to act in the public interest by identifying shortcomings in modelling/communications which may be improved on but also carries the added benefit of potentially opening up career opportunities for the profession.

Concluding comments

Returning to the two “pushback perspectives”, I reiterate they are valid challenges to raise but I trust that my comments above illustrate how:

my manifesto will help to steer the profession in the interests of members (indeed much of it builds on pre-existing work by the IFoA).

my manifesto will help the UK move forwards successfully, by bringing attention to Bad Heuristics which we need to root out of our decision making.

Yet I need to stress that I can only make a success of this initiative with the attention, legitimacy and authority which requires a democratic mandate from my actuarial peers. Therefore I humbly request your support in the Summer 2025 elections.